|

|

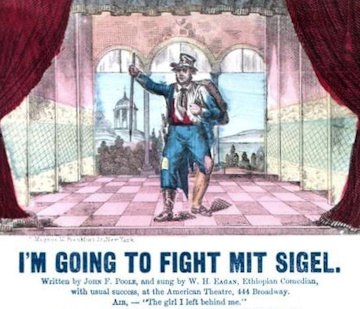

Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel, north-american general, born November 18, at Sinsheim in Baden, died August 21, 1902 in New York. Entered the Baden infantry in 1844 as lieutenant, but took leave in 1847. He participated in the 1848 revolution (Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon 1905)

When in May 1849, during the uprising in favor of the

German Constitution the majority of the Baden Army had joined the

protesters the Grand Duke fled into France. A revolutionary government took

power. Since Sigel was the loyal ex-officer they already

knew and in whom they had confidence they made him chief of the people's

army. Still young and inexperienced the question loomed about Sigel's

qualification. At Laudenbach on the Baden-Hessen border on May 30, 1849, he

lost his first battle against the Hessen army. Sentenced to explain himself

in front of the people's assembly he had no excuse for the defeat:

We have been beaten but the revolutionary army is safe.

His answering ended in the phrase: I have been

beaten but whatever may come I shall never regret to have declared war on

Europe [Beck49]. On that statement he promptly was

Sigel as seen in the States: His Monument at the Riverside Drive in New York

What followed we conveniently read from Sigel's Monument at the Riverside Drive in New York: After settling in New York City in 1852, he taught in public and German schools, co-founded the German-American Institute, joined the Fifth New York Militia, and wrote for the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, and the New York Times. He moved to St. Louis in 1857 to teach at the German-American Institute. At the outset of the American Civil War, Sigel formed a regiment that helped to keep Missouri and the federal arsenal for the Union.

It actually was in April 1861, when 1000 volunteers of the 3rd Missouri Regiment were ready under Colonel Sigel's command and clad in uniforms resembling the revolutionary blouses of 1848 [Kühn10]. Not only Hecker but many old comrades and even a former deputy of the Frankfurt National Assembly had reported ready for duty. Although the majority of the men in his regiment were of German origin other Europeans took up arms for the Union as well, like former Polish freedom fighters, democratic Hungarians and even a regiment of Swiss riflemen.

In his first battle at Carthage on July 5, 1861, Sigel demonstrated what he knew best and what he had learned the hard way as chef of the revolutionary army in Baden: fighting in retreat.

Serving in the Army of the Southwest in Missouri under General Nathaniel Lyon Sigel's brigade fought the battle at Wilson's Creek on August 10, 1861 [Scot70]. Following the General's heroic death Sigel took command of the Union troops and suffered a crushing defeat. There he definitely lost his reputation among the professional officer corps and his ignominious retreat was surely one of the reasons that Iowan Samuel Curtis was preferred as the new commander.

Although Sigel's military achievements had been limited Lincoln appointed him to the rank of brigadier general on August 17, 1861. The President knew that Sigel was popular among the German community. He could and should rally the men around him and Lincoln needed those Germans at the front. (The overall percentage of German fighting men in the Union Army was 9% with the maximum in Missouri of 36% and Wisconsin winning the Silver Medal with 19.8%. These two States were followed by Minnesota 13.6%, New Jersey 12.4% Maryland 11.1% and New York 10.9%.)

The year 1862 saw Sigel in action at Bentonville on March 6, where again he had to fight in retreat. The following days, however, commanding two Divisions under General Curtis he gained a glorious victory at Pea Ridge, a battle Sigel still is venerated for although some experts claim he is honored too much. On March 21, he was promoted to major general of volunteers taking over as John C. Frémont’s successor the First Corps of the Army of Virginia.

However, among his peers Sigel was less than equal. Although hailed by the German written press for his victory at Pea Ridge, West Pointers sneered at him and refused to serve in his Corps: Who is that stranger who flew in from the West? What did he achieve there such that he became one of the first American officers?[Kauf12]. For them he is nothing else than the Dutch general commanding his sauerkrauts.

His commander Major General John Pope was furious and called Sigel the God damndest coward I ever knew [Ston06].

The hostilities of his fellow officers eventually drove Sigel to ask for his discharge. President Lincoln wrote him a personal letter of support so he stayed on but was only entrusted to insignificant commands.

In 1864 seeking his re-election Lincoln wanted to count on Sigel's popularity within the German community. He vindicated Sigel even taking the risk of making him the commander of the new Department of West Virginia. In his new function Sigel opened the 1864 military campaign in the Shenandoah Valley in March. He was soundly defeated by Major General John C. Breckenridge in the Battle of New Market, on May 15, 1864, which was particularly embarrassing due to the prominent role young cadets from the Virginia Military Institute played in his defeat when they overran the Union defense lines [Scot70].

Following his defeat Sigel reported to the Union’s Adjutant General Halleck: The retrograde movement was effected in perfect order. The troops are in very good spirits and will fight another battle if the enemy should advance against us. Did history repeat itself? This time Sigel’s words, however, did not have the same effect as 1849 way back in Baden when he had impressed the people's assembly. Halleck translated Sigel’s words in his way when reporting to General Grant: Sigel is in full retreat on Strasburg. He will do nothing but run: never did anything else [Ston06]. And Strasburg, Virginia was not Strasbourg in Alsace that had been a safe haven for Baden’s revolutionaries in 1849. Sigel was relieved of his field command thereafter and he resigned from the military service on May 4, 1865.

|

||||||||||||||||||

The two other 48ers who came from Baden I want to discuss were military

men: Franz Sigel and Andreas Lenz. Franz had been ousted in 1847 from the

Baden army because he had fought a duel. At that time young Sigel aged 23

was a man of no future with no experience and certainly no military

competence. So he considered studying law when the Baden Revolution broke

out. He joined Hecker in Konstanz on his march to Karlsruhe and even reached

Freiburg with a small detachment before government forces stopped him too.

The two other 48ers who came from Baden I want to discuss were military

men: Franz Sigel and Andreas Lenz. Franz had been ousted in 1847 from the

Baden army because he had fought a duel. At that time young Sigel aged 23

was a man of no future with no experience and certainly no military

competence. So he considered studying law when the Baden Revolution broke

out. He joined Hecker in Konstanz on his march to Karlsruhe and even reached

Freiburg with a small detachment before government forces stopped him too.  made war minister.

When with the Prussian army pushing, the revolutionary government had to

flee Karlsruhe in June 1849, they settled in Freiburg for a short time.

During the apocalypse of the revolution Sigel was among the few remaining

falcons while Struve had turned into a dove. All in vain because on July 7,

1849, the shabby rest of the defeated revolutionary army crossed the river

Rhine into Switzerland.

made war minister.

When with the Prussian army pushing, the revolutionary government had to

flee Karlsruhe in June 1849, they settled in Freiburg for a short time.

During the apocalypse of the revolution Sigel was among the few remaining

falcons while Struve had turned into a dove. All in vain because on July 7,

1849, the shabby rest of the defeated revolutionary army crossed the river

Rhine into Switzerland.